Shared ownership is marketed as the affordable alternative to outright purchase and the private rental sector. But is this claim justified?

Shared Ownership Resources spoke with Joe Elliott, Senior Analyst with the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (an independent social change organisation working to solve UK poverty). We were surprised to see figures which begged the question of whether shared ownership schemes were driving poverty.

Shared Ownership Resources (SOR): Thanks for taking part in this Q&A, Joe. My first question is whether housing choices affect whether people are likely to experience financial hardship, or even poverty?

Joe Elliott (JE): Housing costs are a major factor in determining whether people experience financial hardship. Obviously, the level of household income is also very significant. But our analysis demonstrates that housing costs are a key driver of poverty for renters and shared owners in particular.

SOR: What kind of numbers are we talking about here?

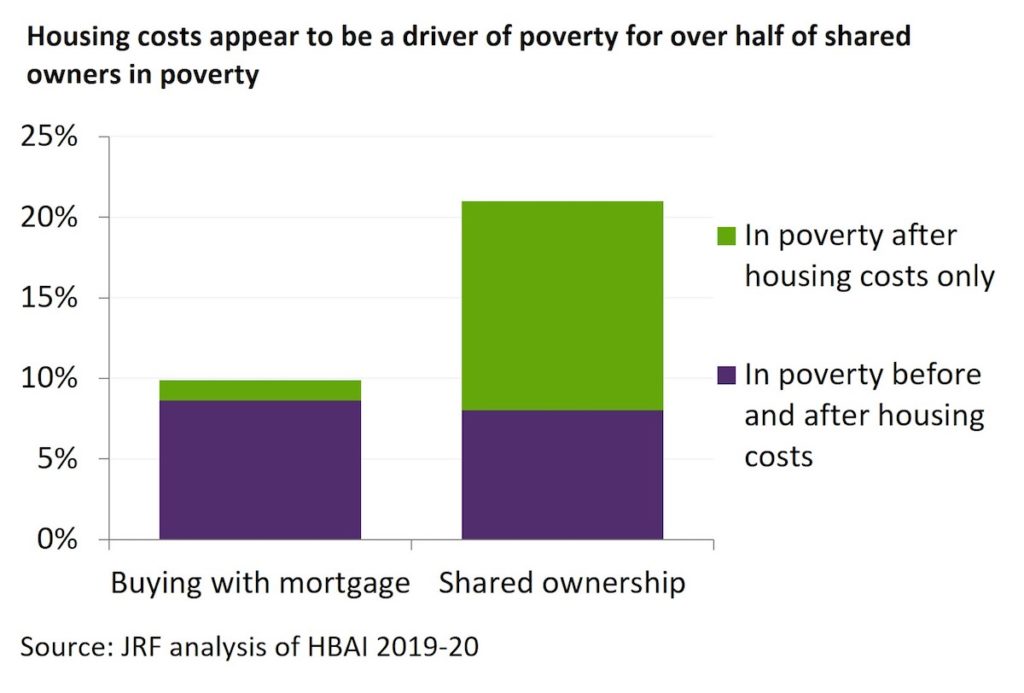

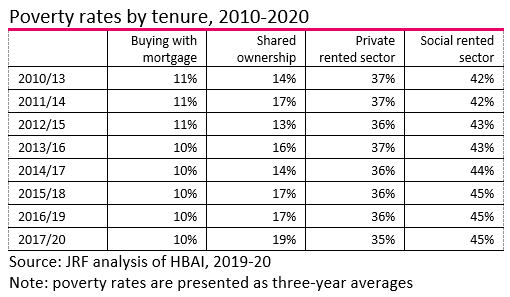

JE: Our analysis for 2019/20 suggests that around a fifth (21%) of shared owners are in poverty. To put that into context, poverty rates are higher for shared owners than for those who own their own homes outright (15%) and households buying outright with a mortgage (10%). But shared ownership poverty rates are lower than for private renters (33%) and social renters (46%).

SOR: You mentioned that housing costs are a key driver of poverty for renters and shared owners. Could you say a little more about this?

JE: Poverty rates are lowest for households who already own outright, or who are in the process of buying outright with a mortgage. When these homeowners experience poverty, housing costs are generally not the cause.

The picture is very different when you look at shared owners and renters.

In 2019/20 the shared ownership poverty rate (21%) was more than double the rate for those buying a home outright with a mortgage (10%). Additionally, for around half of those shared owners, housing costs seem to be the underlying driver for poverty.

When it comes to private renters, we estimate that one-third (33%, 4.2 million people) are in poverty. Of these, around half (46%, 1.9 million people) are pulled into poverty by their housing costs.

Social rental housing is allocated on the basis of need. So you might expect poverty rates to be relatively high amongst social renters. However, around one-third (32%, 1 million people) of social renters are actually pulled into poverty by housing costs.

SOR: I’m shocked at how high poverty rates are across all the various housing tenures. What’s the trend for shared owners over the past decade? Have shared ownership poverty rates increased or declined?

JE: At the moment, there’s too little data to support robust analysis. But the data we have suggests poverty is increasing faster amongst shared owners than for other groups. Between 2010/13 and 2017/20, shared owner poverty rates increased by 5%. The figure for the social rented sector. was 3%, whereas poverty rates actually declined (slightly) for those buying with a mortgage and private renters.

SOR: Are you surprised that poverty rates for shared owners are so high? (Given that the scheme is publicly-subsidised and marketed as affordable housing?)

JE: Shared owners tend to be on lower incomes, compared to households buying outright with a mortgage. After all, shared ownership is targeted at those who can’t afford to buy on the open market.

But it is surprising that around a fifth of those who’ve bought into a Government housing scheme, designed to offer an affordable home-ownership option, will find themselves in poverty. Especially as around half of those are in poverty only after housing costs have been factored in.

SOR: Homes England say that total housing costs are affordable at between 25%-45% of net household income. And the GLA (which is responsible for delivering shared ownership in London) uses a 40% threshold. Presumably initial affordability assessments mean that the costs of shared ownership are below those thresholds when people purchase their initial share. So why are increasing numbers of shared owners in poverty? Does shared ownership actually make households poorer?

JE: This is a complicated area. My view is that % of income to housing costs is an imperfect measure. It can be useful. In fact, JRF used the measure to assess rental affordability for low-income private renters last year.

But different measures would probably provide greater insight in this case. For example, whether households have sufficient income left after housing costs to cover basic needs (the ‘residual income’ measure).

Does shared ownership make shared owners poorer? It’s an important question, and one we don’t have a definitive answer to at present. In our planned programme of housing research and policy development, one of our areas of focus will be on how to achieve a higher rate of homeownership that is sustainable and affordable.

SOR: Unlike private and social tenants, shared owners have to pay 100% of repair and maintenance costs – regardless of the size of their equity share – on top of their rent. Does this contribute to the high poverty rate?

JE: Official poverty figures don’t usually factor in repair and maintenance costs. But it seems likely, given unprecedented increases in the cost of living generally, that service charges on top of rent could drive hardship for shared owners on lower incomes.

And, of course, shared owners facing liability for the costs of building safety remediation, and associated charges such as increased insurance fees and waking watch, experience huge precarity.

SOR: Shared ownership rent starts off on a subsidised basis. (Initial rent is generally 2.75% of the value of the share owned by the housing provider). Do shared ownership rents rise faster than social housing rents, or private rents?

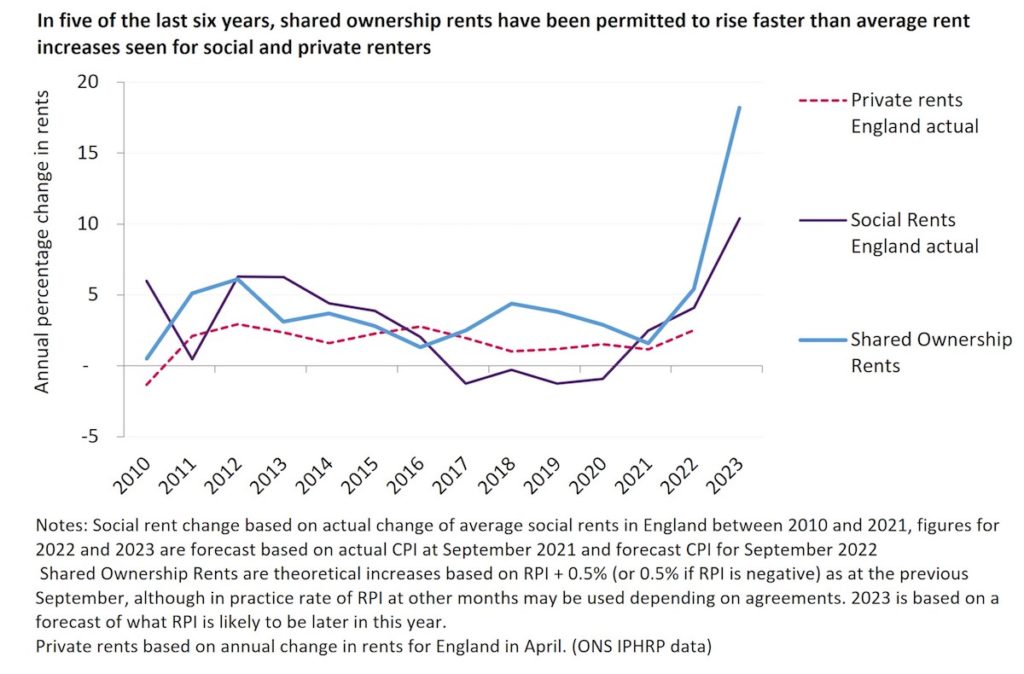

JE: The short answer is yes.

- Let’s take a hypothetical private tenant paying £100 rent per week in 2016. Given the average rental growth, they’d be paying £110 per week by 2022.

- Now let’s take a hypothetical social tenant paying the same rent of £100 per week in 2016. Social renters actually experienced some rent reductions during this period. So they’d be paying £103 per week by 2022.

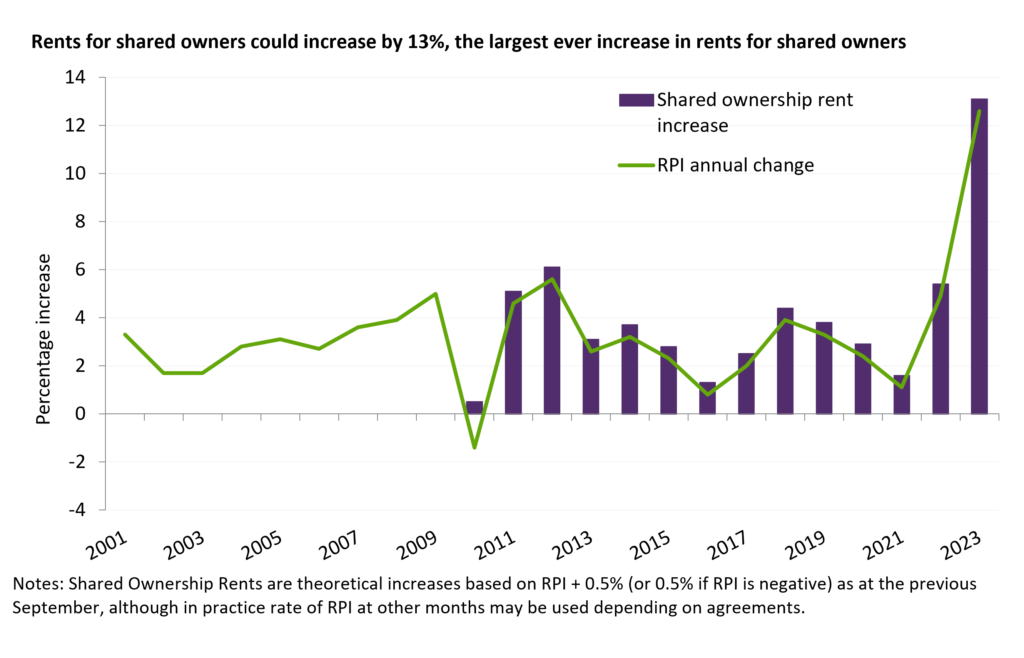

- And, finally, let’s look at a shared owner paying £100 per week in 2016. If their landlord increased their rent in line with the maximum permitted under the current model lease (RPI plus up to 0.5%) they’d be paying £122 per week by 2022.

Looking at this from a slightly different perspective, private sector tenants saw an average 10% increase between 2016 and 2022. Over the same time period, social rental tenants saw an average 3% increase in rent, whereas for shared owners the increase was 22%.

SOR: The National Institute of Economic and Social Research (NIESR) issued a forecast that RPI could rise as high as 17.7% this year. Meaning shared owners potentially face rent increases of 18.2% (RPI plus 0.5%) in 2023. What is the potential impact on poverty rates amongst shared owners?

JE: Many shared owners have already experienced challenging rent increases in 2022. If housing associations increase rents by the maximum permitted in 2023, shared owners could see the highest ever increases, up by a fifth on 2022 rent levels. In fact, this year’s increase in shared ownership rents would be equivalent in size to the increase over the previous six years combined.

EDITORS NOTE: Since this article was first published September 2022 RPI has been published and is 12.6% (up from 12.3% in August). The graph below has been updated accordingly.

A rent increase on this scale would be unaffordable for a great number of shared ownership households. Many were already facing substantial financial challenges before the current cost of living crisis piled even more pressure onto them.

Imposing shared ownership rent increases in line with the maximum permitted by the model lease would be unsustainable, and would drive significant hardship. Recent JRF analysis has found that – since the start of this year – huge numbers of low-income households have been experiencing enormous hardships such as being unable to heat their homes, going without adequate food or falling behind on energy bills and housing costs.

There is a real risk that the perfect storm of spiralling prices alongside increasing interest rates could see low-income shared owners unable to meet their mortgage and rent payments and, at worst, facing repossession.

SOR: The Office for National Statistics (ONS) say:

They add:

SOR: What is the Joseph Rowntree Foundation’s view on the inflation plus policy underpinning annual shared ownership rent reviews?

JE: Again, this is a complex issue. On the one hand, annual rent increases in excess of RPI may result in unaffordable housing costs for shared owners.

On the other hand, complex financial arrangements for the delivery of shared ownership schemes may currently be dependent on assumptions of above RPI rent increases. However, these agreements would have anticipated the inflation rate averaging between 0-5% as it has done for most of the last 25 years, not running into the high teens as it is forecast to reach later this year.

There could be an argument for aligning shared ownership rent increases with social rent increases. But, in the current economic situation, even the social housing rent increase formula (CPI plus 1%) could be unaffordable for a large number of shared owners (as it is for many social tenants). The Government is consulting on capping increases for social rents next April at between 3%-7%. The proposed exclusion of shared ownership from rent caps – despite shared ownership being delivered via an ‘Affordable Homes Programme’ – will inevitably result in shared ownership being anything but affordable for a significant number of shared owners.

SOR: What is needed?

JE: The Government should reconsider exclusion of shared ownership from rent caps as a matter of urgency.

The JRF is also calling for the Government to respond to spiralling energy prices with a comprehensive emergency package to cover the period of extreme price rises, just as they did during the early stages of the pandemic. The crucial tests will be:

- whether help is weighted toward the worst off

- whether it is sufficiently large in scale, and

- whether it covers the period of high prices – which now look set to last into next winter.

Our evidence demonstrates that too often housing costs are an important driver of poverty for low-income households. It is unacceptable that a fifth of shared owners find themselves left with too little income to meet their minimum needs, including meaningfully participating in society.

The Government should consider whether the model of shared ownership requires reform to ensure it is genuinely affordable for shared owners and is not a driver of poverty.

Hi, we’ve been trying to buy the remaining share of our house and we are really struggling to get it over the line. Whilst the value of our house has nearly doubled we don’t seem to be able to get a fair valuation for our improvements. For example, we extended the house yet we are now told the value of the extension is going down whilst the house value has increased. It feels that the whole buying process is staked in the housing association’s favour. Can you offer any advice on this situation?

Thanks for your question. I can understand that normally you would want a valuation to be higher rather than lower; say, in order to maximise your gain if you were selling.

However, if you are staircasing (buying remaining shares) you will benefit from a valuation which is lower rather than higher as this will reduce your cost of staircasing..

The Government makes it cheaper for people to staircase by ignoring improvements in valuations (so long as you’ve obtained permission for any improvements you’ve made). I’ve copied the relevant section from Government advice below.

Hope this is helpful.

Valuations and home improvements

If you have made home improvements which affect the value of your home, the valuation must show 2 amounts:

* the current market value – this is the home’s value including any increase because of home improvements

* the unimproved value – this is the home’s value ignoring any home improvements carried out

If you have your landlord’s written permission to carry out the home improvements, the price of additional shares is based on the unimproved value.

If you did not get your landlord’s written permission, the price of the additional shares is based on the current market value. This price is likely to be higher.

https://www.gov.uk/shared-ownership-scheme/buying-more-shares-staircasing